An introduction to Social Policy

Social security is sometimes used to refer specifically to social insurance, but more generally it is a term used for personal financial assistance, in whatever form it may take. It is also referred to as "income maintenance".

Among many reasons why financial assistance is given, there are:

External link: Social security throughout the world

There are five main types of social security benefit.

The principle behind social insurance is that people earn benefits by contributions, paid while they are at work. The advantages of an insurance scheme are:

The disadvantages are:

Means tested benefits are based mainly on a test of income, though some also include tests of assets or capital. They are extensively criticised in the literature, being seen as the basis of a residual system of welfare.

The advantages of means tests are:

The disadvantages are

This is a broad term which can be used for any non-insurance benefit, but which tends to be used for specifically for non-means tested benefits. Non-contributory benefits based on a test of need are used, for example, for people with physical disabilities, as a form of compensation for severe disability or as a means of meeting special needs (such as a need for social care).

The existence of a test means that the benefits are often administratively complex - in the case of disability benefits, they often require medical examination. Although they avoid a 'poverty trap' in the strict sense there are continuing problems of policing the borderlines and the potential to penalise people whose circumstances improve.

Discretionary benefits are given at the discretion of officials. Because some needs are unpredictable, many social assistance schemes have some kind of discretionary element to deal with urgent or exceptional needs; where social assistance is tied to social work, discretionary payments may also be used as a means of encouraging and directing appropriate patterns of behaviour. Some provision for discretionary benefits is generally seen as a necessity, because it is impossible to provide for every need in advance. However, in circumstances where other benefits are inadequate to meet basic needs, discretionary benefits are liable to be called on more frequently than is appropriate administratively. Frequent use makes the process of claiming an act of personal supplication.

The element of 'discretion' in discretionary benefits varies. In some cases, the 'discretion' is the discretion of an agency; in others, it is the discretion of an individual officer. The basic rationale for discretionary benefits is the need for flexibility, and 'discretion' which is reserved to a large national agency does not always achieve that.

Universal benefits, or 'demogrants', are benefits given to whole categories of a population, like children or old people, without other tests. The benefits are administratively simple, but their wide coverage tends to make them expensive. Proponents of universal benefits have argued for a different type of social security system, a Citizens Income, which would be tax-financed and unconditional. Its proponents argue that it would be simpler, fairer, and would protect those in need more effectively than current systems. Opponents argue that it would be expensive, would undermine incentives to work, and that its apparent simplicity would prove illusory when special circumstances arose.

Paul Spicker talks to the BBC's 'Good Morning Scotland' about universal benefits (MP3 file, 6.3Mb; reproduced by permission)

All benefits have rules, because there has to be some way of deciding who should receive them and who should not. Many have strict eligibility conditions - rules which determine who gets access to the benefit. Unemployment benefits generally require people not to be working - if they did not, they would not be unemployment benefits; penalities for "cohabitation" exist because unmarried couples would otherwise be treated more favourably than married ones. Some rules are there to ration benefits - for example, limiting eligibility for disability benefits by age, or by the severity of the disability.

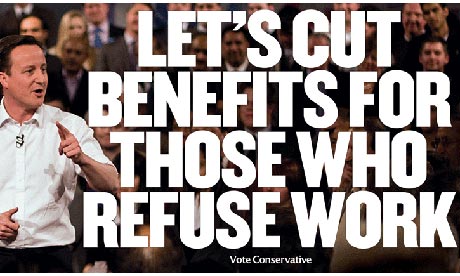

The idea of 'conditionality' usually refers to an additional type of rule, introduced to convey a moral message, to change behaviour, or to punish people for doing the wrong things. Unemployment benefits might penalise people who are unemployed because of 'misconduct' at work. Conditional Cash Transfers have been introduced in several countries (such as those in South America). Typical conditions require mothers to enrol their children in schools and health programmes. There is not much evidence that conditionality changes behaviour; it appears to be most effective where it encourages people to do things they would wish to do anyway, like getting children to school.

External link: Conditional Cash Transfers (World Bank)

Pensions to allow older people to retire developed in many countries not through state action, but through mutual insurance. As governments became involved in the field, they had to decide whether to build on existing pensions schemes, to incorporate them in or to take over. There is no system where pensions are provided entirely by government.

Most pension arrangements take the form of insurance, where entitlement to pensions is determined by contributions. Even if there are contributions, it does not follow that the contributions fund the pension of the person who makes them. Funded schemes invest the contributions in an account, but they are difficult to protect against inflation. Many schemes are ‘pay as you go', or dynamised; contributions now pay for pensions now, and future pensioners will be paid by future contributors. These are sometimes called ‘solidaristic' pensions.

A consequence of relying on contributions is that some people will

not qualify, because they have not paid enough contributions or have

not been living and working in the country. That implies that and there

will need to be a safety net, side by side with insurance benefits.

It follows that pensions typically have three main components, operating in different combinations: a system of private or occupational pensions, typically related to work record and earnings; a government-backed pension scheme, offering basic provision; and a set of safety net provisions.

Disability and incapacity are often confused, but the benefits intended to respond to them depend on different criteria, and the circumstances need to be dealt with distinctly. The kind of disability which is generally being responded to by benefits systems - which is not the full range of circumstances by any means - is likely to be either a physical impairment, or a functional limitation in ordinary activity. Provision for disability in these senses is made many reasons, including

Incapacity, by contrast, refers to the situation where people are

too sick to work, or unable to do work that they did previously.

Disability might be one reason for incapacity, but so might be

sickness, or a range of fluctuating conditions which affect people from

day to day or month to month. The aims of provision for incapacity

include

Where governments fail to distinguish the different circumstances, people have to claim whatever benefit is available - meaning that ill people might have to claim as disabled or unemployed, disabled people might have to claim as unemployed or sick, unemployed people might have to claim as sick or disabled.

The causes of unemployment are complex. Some kinds are long term: technical unemployment happens when people's skills are made redundant. Some are medium term: cyclical unemployment happens because there is inadequate demand to keep production going. Some are short term: frictional unemployment happens because people change jobs or locations. Seasonal work, casual employment and subemployment are patterns of work which lead to people being employed only for short periods at a time.

Exclusion from the labour market takes many forms: some people can

opt for early retirement, further education or domestic responsibility,

and others cannot. If poor people are unemployed more, it is not just

because they are more marginal in the labour market; it is also because

they have fewer choices, and because people who become classified as

'unemployed' are more likely to be poor.

Social security for unemployed people is mainly a form of social

protection: it acts to smooth their income over periods of interrupted

earnings. Governments are also likely to use unemployment

benefits to regulate the labour market, seeking to create incentives to

work or disciplining workers; because the benefits are paid during

recessions, they can also be seen as tools for managing the economy

more generally.

A Jobcentre Plus office, where UK claimants meet 'work coaches' who monitor their 'claimant commitment'.

The main response to unemployment is through economic policy, which addresses the issues by considering the workings of the economy as a whole. General measures to manage the economy have to be distinguished from 'targeted' employment measures. like employment subsidies and wage supplements, intended specifically to affect the labour market. Targeted measures are liable to be inefficient, because they help people who may not have stayed unemployed anyway, or they displace problems to other groups.

Employment services are mainly focused on the unemployed person: they offer , for example, improved information, retraining or work experience, which improves a person's comparative position in the labour market but does not of itself create jobs. Some are based in a view of unemployment as idleness: workfare, in the US, is designed to penalise benefit claimants for not working, on the assumption the claimants have a choice. There are two main approaches in Europe. Activation (an idea from Denmark) seeks to promote active participation in the labour market through motivation and the development of skills. Insertion, or social inclusion (from France) is based on a contract between the individual and society. The 'contract of insertion' made between individuals and the local Commission of Insertion is matched with a responsibility on the Commission to develop opportunities. The EU is now referring to both principles in the form of "active inclusion".

External link: Active inclusion

The details of the Beveridge report are concerned with National Insurance, which Beveridge planned to cover people 'from cradle to grave'. The scheme was based in six 'principles' of insurance:

These objectives were never achieved; the inadequacy and poor coverage of the benefits meant that other benefits had to be filled in, and these systems were administered under different rules by different agencies.

Despite the deficiencies, National Insurance still accounts for over half of the expenditure on social security in the UK. But the failure of the scheme to cover the population led to increasing dependency on means-tested benefits, and in particular the basic benefit - National Assistance, later renamed Supplementary Benefit and then Income Support.

External links: Beveridge report; CPAG on the UK system

For most of the period since 1948, a 'safety net' was provided by

means-tested

benefits: National Assistance, replaced in 1966 by Supplementary

Benefit, and in 1984 by Income Support. Several other benefits,

including Pension Credit, Jobseeker's Allowance, Employment and Support

Allowance, developed on similar lines. These benefits

dispose of only a limited

proportion of all the money spent on social security, but they have

been particularly important, because they guarantee a minimum level of

income for many recipients.

Income supplements are means-tested benefits, available to people

across a

failure wider range of low income. The benefit is withdrawn as people's

income

increases. The most important benefits which

work this way is Universal Credit; it was preceded by Family Credit,

Child Tax Credit, Working Tax Credit, Housing Benefit

and Council Tax Benefit. The

rate of withdrawal is called a 'taper'. Housing Benefit was withdrawn

at 65%; the taper for Universal Credit was 65% at first, then it became

63%, and it is currently being reduced to 55%. That means that

for a net increase in

income of £10, £5.50 is withdrawn. After tax and national

insurance, claimants may well find that three-quarters of any

gain in income is removed.

These benefits have the general problems associated with means

testing - complexity, problems with coverage and the problems of

adjusting to frequent changes in circumstances. The

other fundamental problem is the 'poverty trap'. People who have an

increase in earnings suffer from the withdrawal of benefits as their

earnings increase. This is often represented as a disincentive to work,

but there is not much evidence whether it really has that effect; more

to the point is that it is unfair, with some low-paid earners facing

very high marginal rates of taxation.There have been

particular problems with with the introduction of Universal Credit,

which has been subject to

delay, inflexible processes, unpredictable income streams and a

frequent miscalculations.

Unemployment was initially provided

for

through the Beveridge scheme. National Insurance was intended to deal

with a wide range of marginal employment, including casual labour,

seasonal work and short-time working. It was never intended, however,

to deal with long-term or mass unemployment. As long-term unemployment

grew in the 1970s and early 1980s, unemployed people became

increasingly dependent either on Income support or on alternative

benefits, such as benefits for incapacity or single parenthood.

Unemployment was initially provided

for

through the Beveridge scheme. National Insurance was intended to deal

with a wide range of marginal employment, including casual labour,

seasonal work and short-time working. It was never intended, however,

to deal with long-term or mass unemployment. As long-term unemployment

grew in the 1970s and early 1980s, unemployed people became

increasingly dependent either on Income support or on alternative

benefits, such as benefits for incapacity or single parenthood.

By the mid-1990s, the system had virtually ceased to apply, with only 8% of unemployed males receiving National Insurance. Unemployment Benefit was replaced by Jobseekers Allowance, which has contributory and non-contributory rules, but is principally a means-tested benefit.

Throughout this period there was also an increasing emphasis on trying to engage people in the labour market as the main route out of poverty. The term "welfare to work" refers to a series of measures intended to encourage unemployed people into work, including advice, training and supervision. The programme of "welfare reform" is based on three principles. The first is conditionality, or subjecting unemployed people to sanctions for non-compliance with the rules. The second is personalisation, giving people support to speed their return to work. This kind of individualised response has two main problems: imposing responsibility on benefit claimants for the general lack of employment, and trying to deal with millions of claimants as if they could all be dealt with flexibly and individually. The third principle is contracting out, an attempt to provide services to large numbers of people through engaging private contractors. There have been major problems in getting adequate services this way: contractors have been accused of 'creaming' (picking out only the most likely candidates for placement), 'parking' (not providing services to unlikely prospects but getting credit when they return to work anyway) and playing a numbers games, throwing people at jobs in the hope that some of them will stick.

External link: Dan Finn on local employment services in England

The Beveridge scheme provided for universal pensions at a low level. Pensioners were likely to be on low incomes, and in the 1970s more than half the people in the lowest 20% of the income distribution were elderly.

From the 1950s on, numerous schemes were proposed to offer higher

pensions through earnings-related contributions and benefits. This was

the subject of bi-partisan agreement in the 1970s, and led to the

introduction of the State Earnings-Related Pensions Scheme (SERPS).

Subsequently, however, governments came to feel that this represented

too large a commitment to state pensions: the Conservative government

argued that "it would be an abdication of responsibility to hand down

obligations to our children which we believe they cannot fulfil." They

arranged for SERPS to phase out gradually and sought instead to

encourage more private and occupational pension provision. From April

2002 SERPS was replaced by the Second State Pension, which makes more

generous provision for people on lower incomes and those whose

contributions are incomplete. The final income of pensioners relies

increasingly on individual and independent provision. Nearly

two-thirds of pensioners have some form of occupational pension, and

for half of those the State Pension is less than their private

income.

The remaining third are likely to qualify for means-tested supplements. The Pensions Credit has now replaced the previous means-tested support. The "Guarantee Credit", replacing Income Support and the Minimum Income Guarantee, offers a basic means-tested minimum. The Savings Credit allows extra income to be retained for people within a narrow band of income. It is complicated, and take-up is uncertain.

Tax allowances for children were first introduced in 1909, and Family Allowances in 1945. Titmuss, in 1955, made the important argument that tax allowances and benefits were really two aspects of the same thing, a principle which has gradually gained acceptance since then. Child Benefit, combining the two, was passed into law in 1975 (though, because it was controversial, it was not implemented for two years after that).

Child Benefit is flat-rate, not age-related. The case for age relation is that children become more expensive as they grow older. The case against is that poorer families tend to be those with younger children, mainly because the woman in the family is unable to work; and it is simpler not to relate the benefit to age. The basic arguments for Child Benefit are:

- it is paid to the mother, who may have no other income

- it is not means-tested and takeup is very high (perhaps 99%)

- it is simple to administer

- it avoids problems like the poverty trap and stigma

- it helps to protect the position of the working poor.

The arguments against are:

- it is not well targeted. Poorer families tend to be smaller and younger, but Child Benefit gives most to larger families.

- the redistribution is horizontal - from people without children to people with children - rather than vertical, from rich to poor. Child Benefit may redistribute from a poor single person to a better-off family.

One of the most important objections to Child Benefit has now been removed. For most of its existence, Child Benefit was deducted directly from means-tested benefits, leaving it without value to the poorest families. The system has now been revised so that support for children is now distinct from the rest of the benefit system; it now comes largely from a combination of Child Benefit and Child Tax Credit.

J Millar (ed), 2003, Understanding social security,

Policy

Press

J Millar (ed), 2003, Understanding social security,

Policy

Press

R Walker, 2004, Social security and welfare, Open University Press.

P Spicker, 2011, How social security works, Policy Press

P Spicker, 2017, What's wrong with social security benefits?, Policy

Press

World Bank Group, 2020, Sourcebook on the foundations of social rpotection

delivery systems (476 pages, 6.6 Mb PDF)

Paul Spicker's blog, Social Policy, includes regular updates and comments on social security issues.

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/videos/julian-le-grand-competition-versus-integration-nhs